By Ron Rock MSN, RN, ACNS-BC

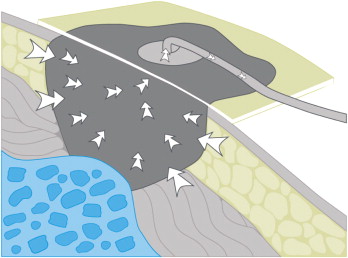

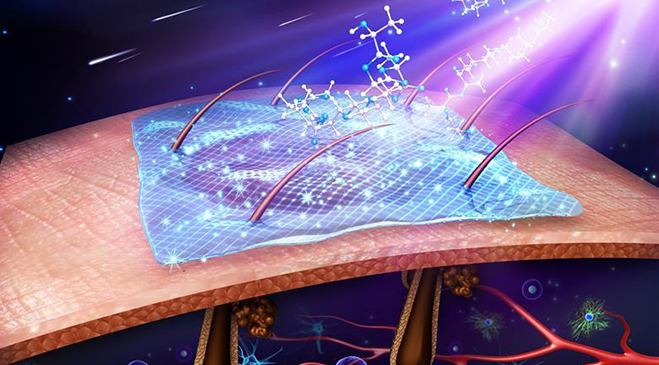

Since its introduction almost 20 years ago, negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has become a leading technology in the care and management of acute, chronic, dehisced, traumatic wounds; pressure ulcers; diabetic ulcers; orthopedic trauma; skin flaps; and grafts. NPWT applies controlled suction to a wound using a suction pump that delivers intermittent, continuous, or variable negative pressure evenly through a wound filler (foam or gauze). Drainage tubing adheres to an occlusive transparent dressing; drainage is removed through the tubing into a collection canister. NWPT increases local vascularity and oxygenation of the wound bed and reduces edema by removing wound fluid, exudate, and bacteria.

Every day, countless healthcare providers apply NPWT devices during patient care. More than 25 FDA Class II approved NPWT devices are available commercially. If used safely in conjunction with a comprehensive wound treatment program, NPWT supports wound healing. But improper use may cause harm to patients. (See Risk factors and contraindications for NPWT.)

Lawsuits involving NPWT are increasing. The chance of error rises when inexperienced caregivers use NPWT. Simply applying an NPWT dressing without critically thinking your way through the process or understanding contraindications for and potential complications of NPWT may put your patients at risk and increase your exposure to litigation.

Proper patient selection, appropriate dressing material, correct device settings, frequent patient monitoring, and closely managed care help minimize risks. So before you flip the switch to initiate NPWT, read on to learn how you can use NPWT safely.

Understand the equipment and its use

Consult your facility’s NPWT protocols, policies, and procedures. If your facility lacks these, consult the device manufacturer’s guidelines and review NPWT indications, contraindications, and how to recognize and manage potential complications. Ideally, facilities should establish training programs to evaluate clinicians’ skills. Enhanced training should include comprehension of training materials, troubleshooting, and correct operation of the device, as shown by return demonstration of the specific NPWT device used in the facility.

Assess the patient thoroughly

The prescribing provider is responsible for ensuring patients are assessed thoroughly to confirm they’re appropriate NPWT candidates. Aspects to consider include comorbidities, contraindicated wound types, high-risk conditions, bleeding disorders, nutritional status, medications that prolong bleeding, and relevant laboratory values. The pain management plan also should be evaluated and addressed.

Assess the order

Before NPWT begins, make sure you have a proper written order. The order should specify:

- wound filling material (foam or gauze dressing and any wound adjunct, such as a protective nonadherent, petrolatum, or silver dressing)

- negative pressure setting (from -20 to-200 mm Hg)

- therapy setting (continuous, intermittent, or variable)

- frequency of dressing changes.

Follow all parts of the order as prescribed. Otherwise, you may be held responsible if a complication arises—for example, if you apply a nonadherent dressing when none is ordered and this dressing becomes retained, requiring surgery for removal; or if you set a default pressure when none is ordered and the patient suffers severe bleeding or fistula formation as a result.

Assess the wound

If you know what your patient’s wound needs, you can take proactive measures. What is the wound “telling” you? With adept assessment, you can become a “wound whisperer”—a clinician who understands wound-healing dynamics and can interpret what the wound is “saying.” This allows you to see the wound as a whole rather than just maintaining it as a “hole.”

- If the wound tells you it’s too wet, take steps to absorb fluid or consider increasing negative pressure, as ordered.

- If it’s telling you it’s dry, consider decreasing negative pressure, as ordered. If the wound bed remains dry, you might want to take a NPWT “time out”. Apply a moisture dressing for several days and assess the patient’s hydration status before restarting NPWT.

- If the wound says it’s moist, maintain the negative pressure.

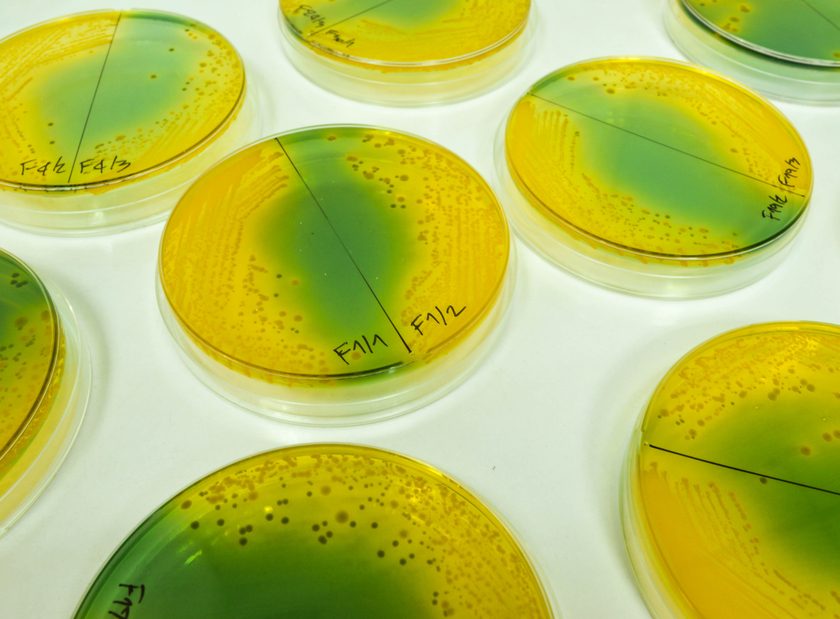

- If it tells you it’s infected, treat the infection.

- If it tells you it’s dirty, debride it.

- If it says it’s malnourished, feed it.

The DIM approach

To establish a baseline evaluation, develop a systematic approach for assessing

the wound before NPWT. This will help optimize wound-bed preparation, enhance NPWT efficacy, and prevent delayed wound healing. (See Assessing with DIM.)

Take a time-out

Before you apply the NPWT dressing, be a STAR—Stop, Think, Act, and Review your action. This time-out allows you to critically think your way through the application process and consider potential consequences of your actions.

Ongoing patient assessment and monitoring

Follow these guidelines to help ensure safe and effective NPWT:

- Follow the device manufacturer’s instructions and your facility’s NPWT protocol, policy, and procedures.

- Identify and eliminate factors that can impede wound healing (poor nutritional status, limited oxygen supply, poor circulation, diabetes, smoking, obesity, foreign bodies, infection, and low blood counts).

- Evaluate the patient’s nutritional status to ensure protein stores are adequate for healing.

- Assess and manage the patient’s pain accordingly.

- Protect the periwound from direct contact with foam or gauze.

- Prevent stretching or pulling of the transparent drape to secure the seal and avoid shear trauma to surrounding tissue.

- Prevent stripping of fragile skin by minimizing shear forces from repetitive or forceful removal of transparent drapes.

- Use protective barriers, such as multiple layers of nonadherent or petrolatum gauze, to protect sutured blood vessels or organs near areas being treated with NPWT.

- Don’t overpack the wound too tightly with foam. Compressing the foam prevents negative pressure from reaching the wound bed, causing exudate to accumulate.

- Position drainage tubing to avoid bony prominences, skinfolds, creases, and weight-bearing surfaces. Otherwise, a drainage tubing related pressure wound may develop.

- Bridge posterior wounds to the lateral or anterior surface to minimize drainage tubing related pressure wounds to the surrounding tissue.

- Count and document all pieces of foam, gauze, or adjunctive materials on the outer dressing and in the medical record, to help prevent retention of materials in the wound.

- Ensure the foam is collapsed and the NPWT device is maintaining the prescribed therapy and pressure at the time of initial patient assessment and when rounding.

- Address and resolve alarm issues. If you can’t resolve these issues and the device needs to be turned off, don’t let it stay off more than 2 hours. While the device is off, apply a moist-to-dry dressing.

- With a heavily colonized or infected wound, consider changing the dressing every 12 to 24 hours.

- Monitor the patient frequently for signs and symptoms of complications.

Evaluate patient comprehension of teaching

A proactive approach to education can ease the patient’s anxiety about NPWT. Unfamiliar sounds and alarms may heighten anxiety and cause unwarranted concerns, so inform patients in advance that the device may make noise and cause some discomfort. An educated and empowered patient can participate actively in treatment. Improved communication may enhance outcomes and help identify errors in technique before they cause complications.

Be prepared to answer patients’ questions, which may include:

- Am I using the device correctly?

- How long will I have to use it?

- What serious complications could occur?

- What should I do if a complication occurs? Whom should I contact?

- How do I recognize bleeding?

- How do I recognize a serious infection?

- How do I tell if the wound’s condition is worsening?

- Do I need to stop taking aspirin or other medicines that affect my bleeding system or platelet function? What are the possible risks of stopping or avoiding these medicines?

- Can you give me written patient instructions or tell me where I can find them?

View: Patient Education

Be a STAR

To avoid patient harm and potential litigation, be a STAR and a wound whisperer. If you’re in doubt about potential complications of NPWT or how to assess and monitor patients, stop the therapy and seek expert guidance. “Listen” to the wound and assess your patient. This may take a little time, but remember—monitoring NPWT, the wound, and the patient is an ongoing process. You can’t rush it. Sometimes, to go fast, you need to go slowly.

Access more information about NPWT.

Selected references

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Technology Assessment: Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Devices. Original: May 26, 2009; corrected November 12, 2009. Available online at: www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/ta/negative-pressure-wound-

therapy/negative-pressure-wound-therapy.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2014.

Daeschlein G. Antimicrobial and antiseptic strategies in wound management. Int Wound J. 2013; 10(Suppl 1):9-14.

Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff—Class II Special Controls Guidance Document: Non-powered Suction Apparatus Device Intended for Negative Pressure Wound Therapy. November 10, 2010. Available at: www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationand

Guidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm233275.htm. Accessed January 30, 2014.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA Preliminary Public Health Notification: Serious Complications Associated with Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Systems. November 13, 2009. Available at: www

.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/

PublicHealthNotifications/ucm190658.htm. Accessed January 30, 2014.

FDA Safety Communication: UPDATE on Serious Complications Associated with Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Systems. February 24, 2011. Available at: /www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/

AlertsandNotices/ucm244211.htm. Accessed January 30, 2014.

Fife CE, Yankowsky KW, Ayello EA, et al. Legal issues in the care of pressure ulcer patients: key concepts for healthcare providers—a consensus

paper from the International Expert Wound Care Advisory Panel©. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2010;23(11):493-507.

Improving the Safety of Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy. Pa Patient Saf Advis. 2011;8(1):18-25. Available at: http://patientsafetyauthority.org/

ADVISORIES/AdvisoryLibrary/2011/mar8(1)/Pages/18.aspx. Accessed January 29, 2014.

Krasner D. Why is litigation related to negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) on the rise? Wound Source. Posted November 11, 2010. Available at: http://www.woundsource.com. Accessed January 30, 2014.

Lansdown AB. A pharmacological and toxicological profile of silver as an antimicrobial agent in medical devices. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2010; Article ID 910686. Available at: www.hindawi.com/journals/aps/2010/910686/

Lipsky BA, Hoey C. Topical antimicrobial therapy for treating chronic wounds. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(10):1541-9.

RG, Goodman L, Woo KY, et al. Special considerations in wound bed preparation 2011: An update©. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2011;24(9):415–36.

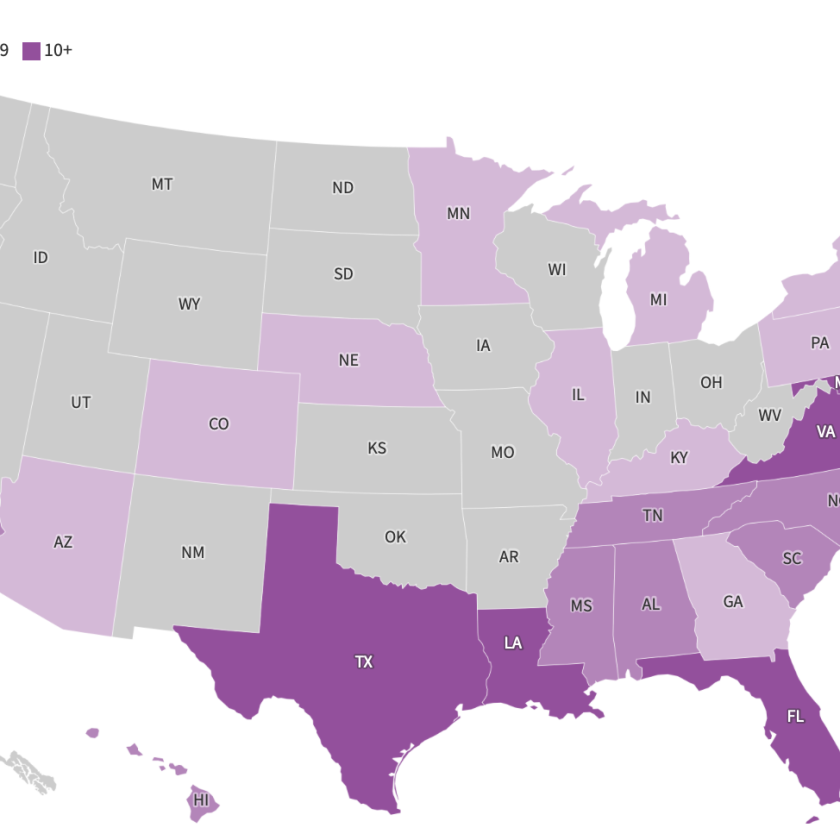

Sibbald RG, Woo KY, Ayello EA. Clinical Practice Report Card: A Survey of Wound Care Practices in the U.S.A. Ostomy Wound Manage. April 2009 Suppl:12-22.

Ron Rock is the nurse manager and clinical nurse specialist for the WOC nursing team in the Digestive Disease Institute of the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio.

DISCLAIMER: All clinical recommendations are intended to assist with determining the appropriate wound therapy for the patient. Responsibility for final decisions and actions related to care of specific patients shall remain the obligation of the institution, its staff, and the patients’ attending physicians. Nothing in this information shall be deemed to constitute the providing of medical care or the diagnosis of any medical condition. Individuals should contact their healthcare providers for medical-related information.

This was an awesome article. I’ve done wound vacs about 10 years and this gave me tips for improved documentation.

Thank you Mr. Rock for a “direct” article regarding NPWT.

From an educator’s and ordering clinician’s point of view, one area that you might want to comment on are the indications and contraindications to NPWT.

What are your thoughts along these lines?

Thank you,

Don Wollheim, MD

NWPT is very effective for wound healing and drainage management, unfortunately, a lot of clinicians, including doctors, do not apply the dressing correctly. Black foam should never be applied to intact skin. Most important is applying transparent drape to skin surrounding the wound right to the wound edge. Dermatitis is common when black foam is applied directly to intact skin. When done correctly, dressing can take 1/2-1 hour to apply correctly.

The indications and contraindications for NPWT follow the specific pump manufacturer’s guidelines. They are relatively standard across the industry. See (Risk factors and contraindications for NPWT.) in this article for a partial listing.

Traditionally NPWT is intended to create an environment that promotes wound healing by secondary or tertiary (delayed primary) intention by preparing the wound bed for closure. It can also prepare a wound bed to receive a muscle flap or skin graft. It reduces local and regional edema, removes exudate and assists with wound contraction as the foam collapses.

Some indications however can be as creative as the ordering clinician or the patient’s specific need. Unfortunately they may go contrary to the manufacturer’s guidelines and therefore must be taken into careful consideration before application to avoid an untoward event. Recognition of potential problems should be thoroughly investigated before NPWT dressing application. In those instances my documentation reflects the goal of therapy; rationale and application procedure. Should there be a compromise in the integrity of the dressing there is an understanding of the clinician’s intent should someone else need to change the dressing.

It can also remove vital proteins; growth factors and MMPs. It can collapse capillaries (if pressures are too high), create a fistula and induce pain. It may not work at all if the inherent ingredients for wound healing are not present within the wound bed. Or the therapy may stall should the body acclimate to the prescribed therapy; tissue becomes hypergranular, a biofilm develops infection, etc…too mention a few. It also does little in the way of debridement.

With judicious preparation and anticipation of potential complications, the indications for NPWT can be impressive. Beyond the well established contraindications…if in doubt…don’t.

I really enjoyed your article-I have been doing vacs for 8 years and you can always learn something new–esp on the documentation end. Thank you

Please advise as to why the NPWT foam must be removed from the wound if the power goes of or it must be discontinued.. I have been unable to find any science or evidence as why this is so.

I have been using NPWT for many years …but I am faced with a dilemma.I have a Patient with a skin condition called Hailey Hailey Pemphigus ( top skin layers fragment) who has a large cavity wound on his buttock which is perfect for NPWT but the Surgeon has said not to use NPWT on a patient with this condition.Has there been any clinical trails done on NPWT with a patient with this skin condition.Apparently it flairs up with physical removal of adhesives that are applied to the skin.I am using hyperfix strips to fixate a dressing on the wound and then soak the hyperfix with a adhesive solvent before removing it so as not to cause any ‘pulling” on the skin.